Does vocationally oriented foreign language teaching meet the needs of Finnish and German vocational school students?

Julkaistu: 13. helmikuuta 2019 | Kirjoittanut: Sanna Dziomba

This article gives a glimpse of student perceptions of foreign language needs versus foreign language teaching in Finnish and German upper secondary vocational schools. In Finland, upper secondary vocational education and training (VET) has traditionally been school-based, whereas Germany has a long tradition of apprenticeship school system. However, since 2018 the Finnish VET is undergoing a big reform moving from a school-based system into a more work-based system, getting nearer to the German system. The reform gives us reasons to make comparisons between these two countries: in which direction should vocationally oriented foreign language teaching go?

Finnish and German educational systems

The interviewed students in the study are upper secondary vocational school students. In Finland, all the students in upper secondary vocational schools have passed primary education where they have been provided with the same amount of compulsory foreign language classes, mostly English. Furthermore, studies in all study programs at Finnish upper secondary vocational schools include compulsory language and communication studies laid down by the Ministry of Education. [1]

The German educational system is more diversified. The main responsibility for the education system lies with the states (Länder), which results in differences among the 16 federal states. After the 4th grade in primary school, pupils enter lower secondary level, where they typically have to choose between Hauptschule, Realschule, Gymnasium and Gesamtschule. VET is provided at the upper secondary level of education and can be entered after completing any of the lower secondary schools. German VET is mainly based on a dual system, which is a combination of theory at school and training in enterprises. [2] According to the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, businesses that are involved in the dual training consider it as the best form of personnel recruitment. [3]

The amount of foreign language classes varies among the federal states and among the different types of schools. The German students in this study come from all lower secondary school backgrounds. In their current vocational schools, most of them have been provided with English classes for half a year, two hours a week. But there are also students of industry mechanics who have not been provided with English or any other foreign language classes by the vocational school. Some of these students have been able to attend English classes in their apprenticeship company, but most of them not.

The Finnish education system has been praised to have no dead ends and to offer equal opportunities for education for all. [4] At the time of the interviews, the Finnish VET was undergoing changes, but the big reform of VET had not come into effect yet. The reform came into effect in January 2018, and its aim is to increase competence-based learning and learning in the workplace (Tammilehto 2017).

Teaching and learning language for specific purposes

English is the predominant language in global business. However, the ability to communicate in multiple languages is an asset in today’s working life where various other languages than English are also used in big transnational organizations as well as in smaller companies. (Holmes 2016, 182–183.) Furthermore, more extensive communication skills are needed in today’s working life where customer service and team work are gaining more importance. Also, in craft professions the amount of customer communication has increased. (Riehl 2017, 3.)

Foreign language learning in VET belongs to a category called language for specific purposes, LSP. Language is a medium to carry out certain roles, e.g. the roles of a nurse or engineer (Huhta, Johnson, Lax, & Hantula 2006, 207). The corresponding term for the English language is English for specific purposes, ESP, which is an umbrella term for English for vocational purposes, EVP (Widodo 2016, 277).

It has been discussed a lot how vocationally oriented foreign language teaching should be constructed: general language skills first or job-relatedness from the very beginning (Kuparinen 2017, 94). Early job-relatedness is in accordance with the principles of Systemic Functional and sociocultural language learning theories. These theories understand learning as participation in situational activities (Dalton-Puffer 2007; García Mayo, Gutierrez Mangado & Martínez Adrián 2013). In addition to participation, Virtanen (2017, 35) also emphasizes the importance of observation: by observing language use situations the learner can acquire the language used in the environment and further develop his or her language abilities.

Research design in this study

The research questions in the study were: (1) How do the vocational school students perceive their foreign language needs in working life and (2) whether and how does the vocationally oriented foreign language teaching currently meet their needs.

35 Finnish and 27 German students participated in the interviews. All students were second-year students who had gained some working experience as a trainee. The students represented various fields of studies: metalwork, business administration, information technology, industry mechanics, electrical engineering, photography, audio-visual media design and physics laboratory. Most students were aged 17–18, but the oldest interviewee was a 27-year-old immigrant woman in Finland. Finnish students all came from the metropolitan area and the German students were both from northern and southern Germany. The data was analyzed by using content analysis.

This article discusses the results of three themes emerging from the analysis: (1) experiences they have made of foreign language needs in working life so far, (2) estimations of foreign language needs at their work in the future, (3) experiences of useful foreign language learning in VET.

Student perceptions of foreign language needs in working life

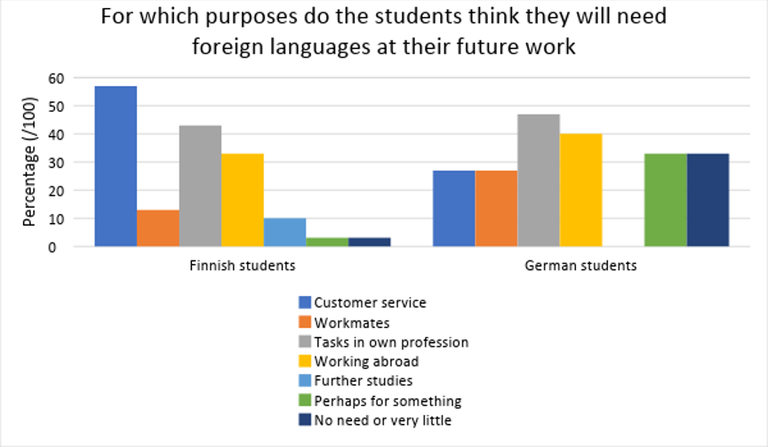

According to the dissertation of Virtanen (2017, 23), successful managing of working life language situations means natural and fluent acting in working life communication situations. My first research question was, what are those working life situations where students think they will need foreign languages, and what are the languages in question. Table 1 below illustrates the answers given by the students:

Table 1: Students’ perceptions of their foreign language needs in working life. The table was drawn after the theme interviews and is based on students’ responses to the topic. The percentage number shows the percentage of interviewed students mentioning the described thing.

Almost all interviewed students had only needed English as a foreign language at work so far. In addition, two Finnish students mentioned Swedish, Russian and Estonian languages. At their future work only a few Finnish and German students expected to need other foreign languages: Russian (2), Swedish (2), Spanish or French (1) or just “various languages” (2). Thus, the English language was clearly seen as the most important foreign language.

During their on-the-job learning periods the students had needed English in customer service, in communication with foreign workmates, in various field-related tasks, and some of them also during a work placement abroad. In the future, students expected to need foreign languages for all these, and in addition, three Finnish business administration students mentioned further studies at higher levels of education.

In the cases where students had had foreign workmates at their own workplace, both Finnish and German students had the tendency to underrate the skills they need in those situations: “It is possible to communicate with hands” or “There are always others to help you out.” On the contrary, if the students had got experience in serving customers in a foreign language, they did not expect others to help them out. Customer service situations might be higher valued among the students than the ability to communicate with workmates in different languages.

In general, the Finnish students see more need for foreign language skills in their home country than the German students do. This might be due to the differences in educational systems and economy sizes. Some German students will have the possibility to later work for the apprenticeship company and they told if staying in one’s home country in the same apprenticeship company, it is not necessary to know English or other foreign languages.

Experiences of useful foreign language learning in vocational school

My second research question was, how well the vocationally oriented foreign language teaching currently meets the needs of the students. Although the needs described here are subjective experiences of students, it is important to know whether the students’ subjectively experienced needs are met: as stated by Herdina and Jessner (2002), motivational factors, perceptual factors and anxiety can be seen as factors determining the rate of change in positive or negative language growth.

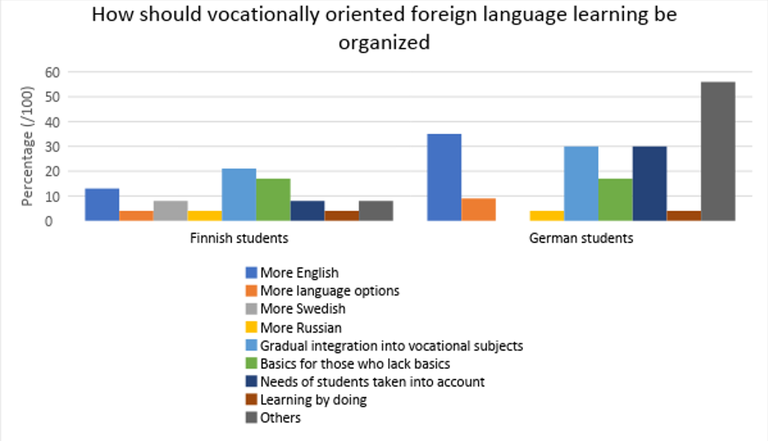

It seems that the students still favor traditional language classes, whether given by the school or like in the case of some German apprentices, by the company. Except for a few skilled language users, they did not wish for more independent learning. One third of the interviewees told that field-related vocabulary is the most important component of useful teaching. The most frequently mentioned task was speaking exercise.

The Finnish students clearly indicated the importance of support given by language teachers and the possibility to progress at one’s own pace. In the autumn 2015, the Finnish national core curriculum in VET was renewed and more emphasis was put on the integration of subjects. Accordingly, some Finnish students had gained experience in integration classes, in which foreign language had been integrated into vocational subject teaching. The way how the integration had been implemented varied a lot, but there were always two teachers, a foreign language teacher and a subject teacher, available. The students often used those classes as examples of useful teaching. However, the integration classes were only seen beneficial if there was enough support available.

The German students often mentioned their employer during the apprenticeship as a possible foreign language instructor. This might again result from the difference in VET systems: since the students can later be employed by their apprenticeship company, they probably value tailor-made language training for the specific needs of the company. The heterogeneous competence levels in foreign language skills due to heterogeneous school backgrounds was often seen as an obstacle for successful foreign language instruction.

Table 2: Suggested changes for vocationally oriented foreign language teaching. All interviewed students did not handle this topic: N=24 Finnish students, N=23 German students. The table was drawn after the theme interviews and is based on students’ responses to the topic.

Conclusions

Educational systems seem to play an important role in students’ experiences. Thus, changes in educational systems should not be done without profound research in advance.

Vocationally oriented English language skills are seen important in both Finland and in Germany. All other foreign languages play only a minor role. Among the German students, even those students who did not think they would need English at their future work would like to have more English language classes available.

The study results suggest that an important motivational element for students to learn vocationally oriented foreign language can be customer service experience. Would it be possible to gain customer service experience also in cases where students’ on-the-job learning period does not include customer service in foreign languages – for example virtual customer service in the internet?

The study contributes to the further development of the reform of VET in Finland. What can the Finns learn from the experiences of Germans? And what can the Germans learn from the Finns?

[1] https://eperusteet.opintopolku.fi/#/fi/esitys/1718932/ops/tutkinnonosat/1719027

[2] https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/Dateien/pdf/Dokumentation/en_2017.pdf

[3] https://www.bmbf.de/en/the-german-vocational-training-system-2129.html

[4] https://minedu.fi/en/education-system

Sanna Dziomba is a PhD student at the University of Jyväskylä currently living in Braunschweig, Germany. She has been teaching vocationally oriented English and German at upper secondary and higher levels of vocational education in Finland for 15 years.

Bibliography

Dalton-Puffer, C. 2007: Discourse in content and language integrated learning (CLIL) classrooms. Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins Pub.

García Mayo, M. d. P., Gutierrez Mangado, M. J. & Martínez Adrián, M. 2013: Contemporary approaches to second language acquisition. Amsterdam; Philadelphia: John Benjamins Pub. Co.

Herdina, P. & Jessner, U. 2002. A dynamic model of multilingualism: Perspectives of change in psycholinguistics. Clevedon, England Buffalo, N.Y.: Multilingual Matters.

Holmes, B. 2016: The age of the monolingual has passed: Multilingualism is the new normal. In: Corradini, E., Borthwick K. & Gallagher-Brett A. (eds.), Employability for languages: A handbook. Dublin: Research-publishing.net, 181–187.

Huhta, M., Johnson, E., Lax, U. & Hantula, S. 2006: Työelämän kieli- ja viestintätaito: Kohti ammatillisen kielen täsmäopetusta. Helsinki: Helsingin ammattikorkeakoulu Stadia.

Kuparinen, K. 2017: Mikä muuttui, kun sairaanhoitajien kielikoulutus siirtyi luokasta työpaikalle? In: J. Lindström & K. Kuparinen (eds.), Yhdessä enemmän. Oppimisen paikkoja ja suuntia. Laurea Publications 87. Laurea-ammattikorkeakoulu, 94–102. Available at: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-799-479-0.

Riehl, C. 2017: Sprache und Kommunikation in der Berufsbildung: Mehrsprachigkeit als Potential. Berufsbildung. Zeitschrift Für Theorie-Praxis-Dialog, 6: 167.

Tammilehto, M. 2017. Reform of vocational upper secondary education. http://minedu.fi/en/reform-of-vocational-upper-secondary-education [retrieved February 8, 2019]

Virtanen, A. 2017: Toimijuutta toisella kielellä. Kansainvälisten sairaanhoitajaopiskelijoiden ammatillinen suomen kielen taito ja sen kehittyminen työharjoitteluissa. Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities 311. Dissertation. The University of Jyväskylä.

Widodo, H. P. 2016: Teaching English for specific purposes (ESP): English for vocational purposes (EVP). In: W. A. Renandya & H. P. Widodo (eds.), English language teaching today: Linking theory and practice (pp. 277–291). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG.