Developing an integrated Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) pathway in Central Finland

Julkaistu: 14. joulukuuta 2017 | Kirjoittanut: Josephine Moate

The recent revisions of core curricula for early years, comprehensive and senior school education in Finland highlight the value of language/s as part of identity, a tool for learning and a means of widening and deepening pupil engagement with the wider world (OPH 2014; 2015; 2016). Highlighting the role of language also supports the notion of an integrated curriculum with thematic units of work cutting across subject and age boundaries. These developments complement the efforts of educators in Central Finland to develop an educational pathway that integrates content and foreign language learning from day care to senior school and beyond. This paper begins by briefly introducing this community and the CLIL educational pathway developed in the early years of the community. The second half of the paper presents a recent community discussion in which the model of the CLIL educational pathway was used as a tool to reflect on CLIL in different contexts and to identify areas for further development.

The Jyväskylä CLIL Cascade teacher community was established in 2009. The individual partners (Kortesuo daycare centre, Kortepohja primary school, Viitaniemi school, Jyväskylän lyseo) had been working for a number of years to individually develop CLIL. The aim of the community was to strengthen the work of teachers and pupil experiences. The notion of a pathway was intended to depict continuity for pupils as they move from one partner to the next and to better support the arrival of newcomers at different points along the pathway.

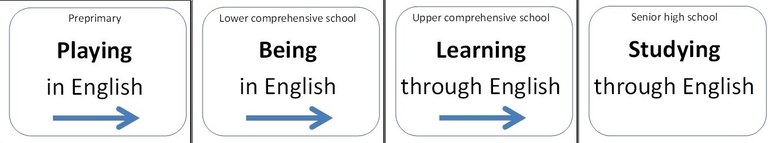

In November 2009 representatives from each partner volunteered to meet for one day to develop the pathway, and funding from the city of Jyväskylä provided substitute teachers for the representatives. This pathway was then shared with the wider community for comments (see Moate 2014 for more detail). This model aims to recognise the needs of pupils as language learners at different ages in different contexts, and is encapsulated in the notions of playing in English, being in English, learning through English, and studying through English. The pathway reflects the notion of a transitional dynamic (Moate 2011) in that during the different phases pupils language abilities are intentionally moved forward towards the next phase, but the pathway also concretises the foundation of language learning.

Figure 1: A pathway for CLIL

Revisiting the CLIL pathway

Since developing the pathway in 2009, the community has continued to evolve with different teachers showing interest in the community, the introduction of the new curricula, as well as staff and structural changes. In May 2017 the community reconvened to discuss the CLIL pathway in the light of the new curricula and whether the pathway continues to represent and support the work of the different partners. The next section introduces the initial model in more detail as well as the additions and new questions that arose during the discussion in May. We hope that this pathway is of use to others.

Pre-primary: Playing in English

In the initial pathway, playing was foregrounded as the key characteristic of integrating foreign language learning within pre-primary education through the use of routines, songs, stories and rhymes. The aim was to develop confidence in hearing and interacting through English, to foster the natural enthusiasm of the children and to support their readiness to think in English in problem-solving and making connections. Returning to these notions, these considerations were further developed. Playfulness now included playing with the language, trying out words and new sounds and routines were more clearly specified as daily routines that involve managing the basics, such as eating together, going outside and coming inside. These routines support community building and socialisation into sharing life together and running these routines in English weaves the additional language into the heart of activities in this setting.

The pre-primary representatives observed how excited the children are to learn a new language - and not only English, but also German as part of the city’s initiative to provide language showers for young learners. All of the partners also commented on the increasing number of bi- and multi-lingual children in their contexts, noting that these pupils rarely seem to struggle with the presence of English in the environment although there is an awareness of the need to be sensitive to children’s experiences, especially when introducing something new.

Lower comprehensive education: Being in English

In grades 1–6 being in English was intended as a way of building confidence and skills in English through regular exposure to the language. The use of English in daily classroom routines and communication, as well as in the use of basic subject vocabulary continue to be seen as practical ways of using English as a tool without it becoming a burden. As the range and depth of exposure to English increases, it is hoped that these practices support the development of English as part of pupils’ individual identities. In the initial model, playing was added when the whole community met to discuss the different stages of the pathway. In the recent discussion playfulness was also added - playfulness with words and phrases, a readiness to take risks and to actively seek language. In this way playfulness contributes to the development of an active learning community that encourages participation, although how to use different strategies to participate and to tolerate uncertainty continue to be areas for development.

As the partners discussed CLIL in the lower comprehensive school, it was acknowledged that language becomes increasingly abstract as subjects become part of the curriculum and part of CLIL activities, just as language becomes increasingly abstract in mother tongue mediated lessons (Lwin & Silver 2014). This highlights the importance of meta-awareness of how language is being used and indicates how foreign-language mediated activities can complement teaching and learning in Finnish. Using another language, for example, is one way of looking from different perspectives and expanding a topic such as how hobbies change with seasons and geographical locations. CLIL-based activities have also supported collaboration between English-medium and Finnish-medium classes as the pupils have carried out combined projects and both English and Finnish languages have been used as resources. Combining two classes for project work, however, requires different kinds of spaces although mixing classes is a useful way of helping pupils to learn to work with new people and ensuring that activities are appropriately challenging. Whereas the early years’ educators were wondering about when to introduce more formal and text-based language use, the primary educators were critically considering when to introduce written language and to development writing skills.

Upper comprehensive education: Learning through English

For the CLIL Cascade partners representing grades 7–9, CLIL activities are mainly associated with the English-medium classes with theoretical subjects taught in English and practical subjects taught in Finnish, integrated with Finnish-medium groups. At this stage English is not only regularly present in the classroom; it is also the language of instruction and learning. Although confidence-building remains an important consideration, the increased focus on the subject in terms of vocabulary development, critical thinking and concept building highlights the importance of the foundational work from the earlier stages of the pathway. General language skills enable pupils to follow instructions and to communicate, but in grades 7–9 pupils need to develop theoretical understanding.

In the recent discussion, the participants noted the importance of developing pupils’ meta-knowledge, such as information seeking skills in order to support the use of language within subject studies. Moreover, the emphasis on integration in the new curriculum makes it possible to develop thematic units of study that require the use of different types of text and forms of language within and around a chosen topic. This means that pupils can use subject-specific terminology across classes and have opportunities to critically consider the way in which different subjects use language in different ways. Successful integration, however, requires coordinating units of work between teachers and teachers to understand the way in which language is used in their subject. Another challenge is to balance the relationship between Finnish and English. Currently the curriculum recognises only one mother tongue, yet it might be that students learning in this kind of environment have advanced language skills in Finnish and English and ideally this would be reflected in the curriculum and activities of different language classes.

Upper secondary school: Studying through English

Previously the pre-IB programme which prepares for the International Baccalaureate (IB) was the finishing point to CLIL in Jyväskylä prior to studies in higher education. The pre-IB programme is designed to support academic study through English as students engage in critical thinking and advanced subject studies that require a high level of vocabulary and productive language skills. In autumn 2017, however, a new bilingual stream has been introduced for grades 10–12 which is based on self-selection, rather than via an entry test a prerequisite for the IB. This bilingual stream will also involve the development of academic language skills, including research, critical reading, argumentation, accuracy, and looking from different perspectives. The emphasis, however, will be on strategic language use encouraging participants to draw on all the language skills they can. This development expands options for high school students in the locality and benefits from initiatives to co-teach courses already introduced into the high school setting.

Concluding discussion

During the discussion a number of themes or questions arose which, as yet, remain unanswered. These themes include the role of expert others as support and a means of authenticating the use of the foreign language, the role of the mother tongue and other languages, and the challenge to maintain a low threshold for and different forms of participation in order to ensure that all pupils can participate. These themes highlight the way in which educational innovation is located within educational communities - different participants have different roles, histories and resources. For an educational innovation to benefit the overall community, these differences have to be recognised and negotiated in order to enrich the community.

There was also discussion around the relationship between CLIL and formal language study especially as CLIL often seems to challenge the norms of conventional language education. Practical issues also became part of the discussion such as what and how to assess bilingual education, as well as the awkwardness of being obliged to give reports in Finnish to non-Finnish speaking parents, what and how to assess in bilingual streams and how to support learning in both languages as well as the development of critical literacy skills. The participants also wanted to be sensitive to the developing language and cognitive skills of their pupils and to provide adequate challenge and support for identity development, as well as academic study or socialisation in school life. The range of issues here indicates the need for ongoing discussion not only within this community, but also within the wider educational community. The current curricula provide an important opportunity to validate the range of languages that are present within local communities, and encourage educators to consider how languages - English as a foreign language, different heritage languages and Finnish can become part of the educational landscape. This is an opportunity we cannot afford to miss.

Acknowledgements

With grateful thanks to Kristiina Skinnari, Gwyneth Koljonen, Taina Nupponen, Susanna Soininen, Ulla Iso-Ahola and Anna Jörgensen for your participation in the discussion, sharing your experiences and insights and for contributing to the development of this text.

Josephine Moate is a senior lecturer in education in the Department of Teacher Education at the University of Jyväskylä. Josephine is responsible for the JULIET programme which specialises in preparing class teachers to work as foreign language educators in the lower school. Josephine is also involved in the development of a new study programme KiMo, Kielitietoinen monikielisyyttä tukeva kielipedagogiikka, a cross-departmental programme at JYU.

References

Lwin, S. M. & Silver, R. E. (2014). What is the role of language in education? In R.E Silver & S.M. Lwin (eds.), Language in education: social implications. Bloomsbury Academic A&C Black: London, 1–18.

Moate, J. (2011). Reconceptualising the role of talk in CLIL. Apples - Journal of Applied Language Studies. 5(2), 17–35.

Moate, J. (2014). A narrative account of a teacher community. Teacher Development, 18(3), 384–402.

Opetushallitus (2014). Perusopetuksen opetussuunnitelman perusteet 2014, Juvenes Print - Suomen Yliopistopaino Oy, Tampere.

Opetushallitus (2015). Lukion opetussuunnitelman perusteet 2015, Juvenes Print - Suomen Yliopistopaino Oy, Tampere.

Opetushallitus (2016). Varhaiskasvatussuunnitelman perusteet 2016, Juvenes Print - Suomen Yliopistopaino Oy, Tampere.