Education Export in Basic Education in Finland: South Korean Elementary Pupils’ Positive and Challenging Experiences

Julkaistu: 22. maaliskuuta 2023 | Kirjoittaneet: Farzaneh Kamali Vinne, Ritva Kantelinen, Calkin Suero Montero, Zinab Elgundi ja Hanne Partanen

Introduction

Education export is a fast-growing phenomenon in Europe and world-wide. In Finland, education export represents a core asset for achieving the country’s goal of becoming one of the world’s top education-based economies (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2010, p. 3; Schatz, 2016). In the Finnish context it is defined as “an intentional business transaction concerning educational practices, services, and materials from one country to another” (Schatz, 2015, p. 330). This transaction can be realized through pupils, teachers, researchers, and other education experts a) from Finland going abroad to share ideas and training, and/or b) from abroad coming to Finland to receive training and observe the implementation of local educational practices.

The Education Export Happy Learning in Outokumpu project, hence, piloted the education export ideas bringing to Finland teachers and pupils from South Korea. The project aimed at supporting basic education export, boosting elementary school pupils’ joy, and fostering transversal competences’ development in a pleasant and convivial atmosphere.

Implementing the project, in August 2018, ten South Korean elementary pupils aged 11-12 years (fifth and sixth graders) together with their four teachers, were hosted at Kummun Koulu, Outokumpu, Finland, for twelve days. For their visit, all activities were designed based on the Finnish National Core Curriculum for Basic Education 2014 concept of transversal competences (Finnish National Agency for Education, 2016). The activities included four to six hours of school classes with local pupils of the same grade and age, and afterschool and weekend activities designed to broaden pupils’ cultural experiences in Finland, e.g., visit to Koli National Park, fishing.

The language of communication was English, and this was the only language used among South Korean pupils during the project activities, although Finnish was also used among the Finnish pupils. Multiculturalism and multilingualism were strongly evident throughout the Happy Learning Project. The project provided an opportunity for the pupils to experience sharing knowledge and studying together at a local Finnish school.

To examine if the pilot project succeeded in achieving its goals, data were collected and analyzed. We mapped the transversal competences to the positive and challenging experiences the pupils reported. Therefore, we answered the following research questions:

-

What positive experiences did South Korean pupils have?

-

What challenges did South Korean pupils face?

-

How do these positive and challenging experiences map into transversal competences?

Conceptualizing Transversal Competences

Global education is highlighted in the Finnish National Core Curriculum to provide conditions for fair and sustainable development for children to enjoy their lives and learn necessary skills to become happy adults (Finnish National Agency for Education, 2016, p. 30.; Layard & Haggel, 2015). A transversal competence refers to “an entity consisting of knowledge, skills, values, attitudes and will” (Finnish National Agency for Education, 2016, p. 33). There are seven transversal competence areas taking the age of pupils into account to support their growth as human beings:

I. Thinking and learning to learn. Pupils’ thinking and learning is influenced by how they perceive themselves as learners and how they interact with their environment.

II. Cultural competence, interaction, and self-expression. Pupils are supported in recognizing cultural meanings in their living environment and appreciating cultural diversity based on respect for human rights.

III. Taking care of oneself and managing daily life. Pupils are encouraged to think positively about their future and learn how to take care of different areas influencing their daily life e.g., health, human interactions, finances.

IV. Multiliteracy. Pupils are supported to acquire knowledge about different modes of cultural communication and their own personal identity.

V. ICT Competence. Pupils are guided to understand key concepts of information and communication technology (ICT), to use it safely.

VI. Working life competence and entrepreneurship. Pupils are assisted to learn and create a positive attitude towards work and working life.

VII. Participation, involvement, and building a sustainable future. Pupils are facilitated to learn the importance of the knowledge they gain through participation in civic society, decision-making and responsibility. (Finnish National Agency for Education, 2016, pp. 33-37).

Method

Primary data were collected through triangulation (Gorard, & Taylor, 2004, p. 43; Flick, 2007, pp. 80-81). Since pupils’ voices were the key element to deduce whether the project was successful in achieving its goals, we used observations, semi-structured face-to-face interviews, and written diary entries of the ten participating South Korean pupils, as data. This multimodality increased the data validity and reliability. The pupils participated voluntarily in the data collection process and consent was received from them and their parents or guardians. 151 minutes of audio recorded semi-structured interviews conducted in English were transcribed and analyzed. To guarantee the anonymity of the participants, we use pseudonyms in this paper.

South Korean Pupils’ Positive Experiences

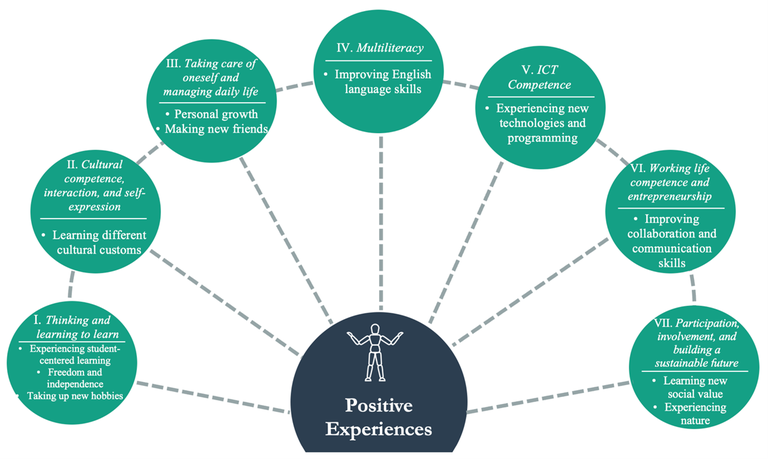

Figure 1 illustrates the positive experiences of the South Korean pupils seen through the seven transversal competences.

Figure 1. South Korean Pupils' Positive Experiences in Happy Learning Project

In line with transversal competence I. Thinking and learning to learn, the positive experiences that South Korean pupils described referred to a) student-centered educational activities, b) having trust in themselves to try out new things, c) learning new things and using them independently, and d) teachers’ support in building trust. Sofia, for instance, was interested in Finnish student-centered education:

“I realized that the school focuses on students and it’s like students are the most important thing in school in Finland.”

Regarding II. Cultural competence, interaction, and self-expression, the pupils were given the opportunity to get to know different cultural customs and heritages. The respectful attitude towards other people from different countries was something that caught one pupil’s attention, as Sofia wrote in her diary:

“Many people from all over the world came to Kummun koulu. I got to experience many different cultures of different countries. I succeeded in learning the main point of today. Even though we are from different countries, we can all get along together.”

As stipulated in competence III. Taking care of oneself and managing daily life, education should support children in developing various skills and encourage them to communicate and interact with even limited language skills (Finnish National Agency for Education, 2016, p. 34). In relation to this, Adam stated how worried he was regarding making friends before coming to Finland and how during the project he learnt all they needed was a common interest like football to communicate:

“I was obviously excited and, but I was actually pretty nervous because it would have been bad if I didn't make any Finnish friends […] But it turned out not like that. We just played soccer and we became very, like, partly friends […] and I think soccer did everything.”

The aims of IV. Multiliteracy was supported, since English, the common language between Finnish and South Korean pupils, was a language other than their own mother tongue. Most South Korean Pupils showed huge enthusiasm in talking in English and learning Finnish as well as other languages. Elvis, for instance, even tried to share the gained knowledge by using the newly learnt language:

“I learned little bit language, Finland’s language, Hei, Hei hei and Kiitos”.

Regarding V. ICT Competence, programming and the use of a 3D printer were the most often mentioned ICT activities that South Korean pupils enjoyed (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Pupils testing 3D printing

In line with VI. Working life competence and entrepreneurship, learning through group work in various activities was highlighted by the South Korean pupils. Dylan described how they collaborated when planting trees in groups:

“Two people worked together, one for digging and one for planting” (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Pupils experiencing tree planting

Learning in different social environments as well as gaining essential skills for participating in civic activities are the focus of competence VII. Participation, involvement, and building a sustainable future. For Mila, for instance, it was a positive experience to learn to pick berries herself and learn which ones are safe to eat:

“I liked picking berries because like, in South Korea we don't have like real berries in the nature, we just buy them.”

South Korean Pupils’ Challenging Experiences

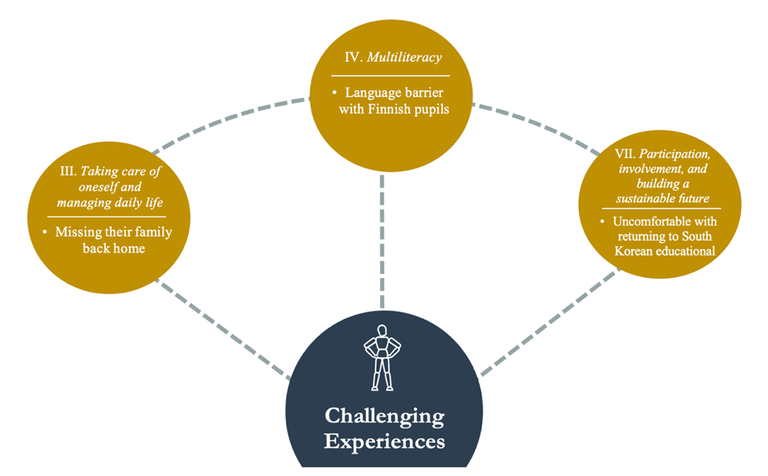

The challenging experiences of the South Korean pupils are summarized in Figure 4, seen through the transversal competences’ lens.

Figure 4. South Korean Pupils' Challenging Experiences in Happy Learning Project

One challenge mentioned by the pupils was missing their parents, which can be linked to competence III. Taking care of oneself and managing daily life. Several pupils stated that they had been anxious about being far from their family before the trip, but that it was easier to handle after their arrival in Finland. Although they were all happy about being in Finland and wished to stay longer, they mentioned that they wanted to go back to South Korea because they naturally missed their parents, as expressed by Sara:

“I’m really happy to my decision [to come to Finland] but actually I miss my mom and dad.”

In terms of IV. Multiliteracy, having different English language proficiency levels made it challenging at times for the Finnish and South Korean pupils to interact, cooperate, and communicate with one another efficiently. Dylan stated his dissatisfaction with this language barrier in his diary:

“We made a group with Finland friend but Finland friends just say with Finnish language so we cannot talk many thing, so it is not good.”

Linked to VII. Participation, involvement, and building a sustainable future, an additional challenge arose out of the self-assessment of the learning environment by South Korean pupils. While the pupils did not refer to the opportunity of comparing two educational systems as a challenge and were thrilled to take part in the pilot project, they were worried that it might be a challenge to go back to their routine in South Korea afterwards. With this new educational experience and learning how pupils in Finland might not have as busy schedules as they do, South Korean pupils worried that they might need to readjust to school back home. When Adam was asked if he would recommend the project to friends, he said:

“It would be great to relax for a while in the sauna, no academies. But maybe they [future pupils] will have a hard time when they go back to South Korea, so is it good or is it bad, that's the problem.”

Overall, compared to the numerous positive experiences during the pilot project, South Korean pupils reported fewer challenges during their stay in Finland.

Conclusion

The findings presented in this article indicate the project’s success in achieving its goal of fostering transversal competences and boosting the joy of learning in the visiting pupils, which provides positive evidence towards the implementation of basic education export in Finland. The findings also highlight areas of improvement.

For future implementations, strategies should be developed to motivate both local and visiting pupils to confidently use their multilingual skills in order to minimize the language barriers. Moreover, guided group discussions comparing Finnish and visitors’ learning environments and educational systems would be beneficial so that pupils’ newly made discoveries and assessments could be shared with peers and teachers on how to deal with and integrate them into their future plans. Also, though the South Korean pupils could talk to their families every morning, there was a challenge related to them missing their families. This could be addressed as a growth opportunity towards becoming more independent and developing the pupils’ interpersonal skills in future implementations.

To conclude, this paper presented a first step towards developing education export in Outokumpu through the Happy Learning Project. The planning phase of the project was partly funded by the Regional Council of North Karelia. We argue that the added value of such education export projects is not only found in economic growth but also in internationalization for individuals and communities involved in the project at various phases (e.g., Venhe, 2019). Further studies with a wider scope are yet needed, including the voices of local pupils and the perspectives of various stakeholders within the education export field keeping in mind that an attitude of mutually beneficial collaboration opens the door to a world of opportunities.

Farzaneh Kamali Vinne is a PhD student in Educational Studies, University of Eastern Finland, School of Applied Educational Science and Teacher Education.

Ritva Kantelinen is a Professor of Education, especially language pedagogy, University of Eastern Finland, School of Applied Educational Science and Teacher Education.

Calkin Suero Montero is a Docent and Senior Researcher, University of Eastern Finland, School of Educational Sciences and Psychology.

Zinab Elgundi is a Global Education Designer, University of Eastern Finland, School of Applied Educational Science and Teacher Education.

Hanne Partanen is a Classroomteacher at Kummun Koulu E-9.

References

Finnish National Agency for Education. (2016). National core curriculum for basic education 2014. Finnish National Agency for Education: Publications 2016:5.

Flick, U. (2007). Designing qualitative research. Los Angeles, [Calif.]; London: SAGE.

Gorard, S. & Taylor, C. (2004). Combining methods in educational and social research. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Layard, R. & Hagell, A. (2015). Healthy young minds: Transforming the mental health of children. World Happiness Report. Available at: https://www.mhinnovation.net/sites/default/files/downloads/resource/WISH_Wellbeing_Forum_08.01.15_WEB.pdf

Ministry of Education and Culture. (2010). Finnish education export strategy: Summary of the strategic lines and measures. Publications of the Ministry of Education and Culture. Available at: https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/75524/okm12.pdf

Schatz, M. (2015). Toward one of the leading education-based economies? Investigating aims, strategies, and practices of Finland’s education export landscape. Journal of Studies in International Education, 19(4), 327–340. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315315572897

Schatz, M. (2016). Education as Finland’s hottest export? A multi-faceted case study on Finnish national education export policies. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland]. Research Reports of the Department of Teacher Education 389. Available at: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-51-2092-2

Venhe, N., 2018. A summer school can change the world. UEF BULLETIN, 12/2019 (pp. 38-39). Available at: https://www.uef.fi/en/article/a-summer-school-can-change-the-world