“Ihmisiltä poissa” – away from people: Language learning spaces in Finnish as a foreign language students’ chat during the covid-19 pandemic

Julkaistu: 9. syyskuuta 2020 | Kirjoittanut: Elisa Räsänen ja Anu Muhonen

Introduction

Phone applications and access to mobile devices broaden the spectrum of students’ possible learning spaces (see Neumeier 2005: 175), which can expand on their language learning experience. This article focuses on the discourse enabled by a mobile app, which allowed students to connect with peers and practice language learning in different spaces and environments. In our pedagogical collaboration, second year students of Finnish at Indiana University and University of Toronto chatted informally during spring semester 2020 as a course assignment. The task was simple: to chat informally about self-selected topics in Finnish. This assignment was graded based on active participation only. The objective for the project was to enhance networking, interaction, authentic language use, and incidental learning (see Kelly 2012). The chat was administered by a teaching assistant but led by the students and conducted in the free mobile phone app Kik.

During the 11-week-long collaboration, both Finnish programs switched to remote instruction due to the covid-19 pandemic. While the pandemic did not affect the chatting task much, it did have an impact on the conversation topics. Students were mostly obliged to stay at home due to physical distancing, and many of the corona-time chatting was done in isolation, as the quote “Ihmisiltä poissa” <away from people> in the title indicates. In this article, we analyze selected chat excerpts students shared from home and surrounding environments during the pandemic. We analyze how language learners discuss these spaces in the chat.

Chat conversations have been widely studied in the second and foreign language context from different viewpoints (see, for example, Lai 2016, Li 2018, Wigham & Chanier 2015). Previous studies have also investigated the use of mobile apps in Finnish as a second/ foreign language learning. Lilja and Piirainen-Marsh (2016, 2019) explored Finnish as a second language learners’ interactions “in the wild”; the use of mobile phones allowed students to record the interactions which were later analyzed in the classroom. Komppa and Kotilainen (2019) analyzed the implications of a speech recognition app Appla in outside-of-class language learning. Vaarala and Bogdanoff (2019) looked at adult literacy learners’ free time use of mobile devices. They reported that learners use these devices for multiple different purposes, which could also be utilized as a resource in formal language learning. Bogdanoff, Vaarala and Tammelin-Laine (2019: 7) report on an adult literacy learners' WhatsApp chat group, which was used for sharing course work, and students also engaged in informal conversation. Räsänen and Muhonen (2020) focus on community building in Finnish language learners’ Padlet chat; while students shared glimpses of their everyday lives and commented on each other’s productions they also expressed belonging to a supportive community of learners.

This article applies a data-driven approach. The data consists of 517 chat entries, which include written text messages, photos, memes (gifs and still images), videos and emojis. Altogether 7 students from both universities, 1 teaching assistant and 2 instructors participated in the chat. The names of the participants have been removed and the data has been further anonymized.

Chatting from home, backyard, and home street

Home was the place where students spent most of their time during coronavirus distancing. In our analysis we concentrate on the chat entries related to students' homes, home streets and hometowns. In the chat, students invited peers to many private spaces typically inaccessible to classmates. The convenience of the mobile chat enabled sharing at times convenient for the students, and we observed that the first chat entries in the morning started from the breakfast table, and in their last posts in the evening, students wished each other goodnight.

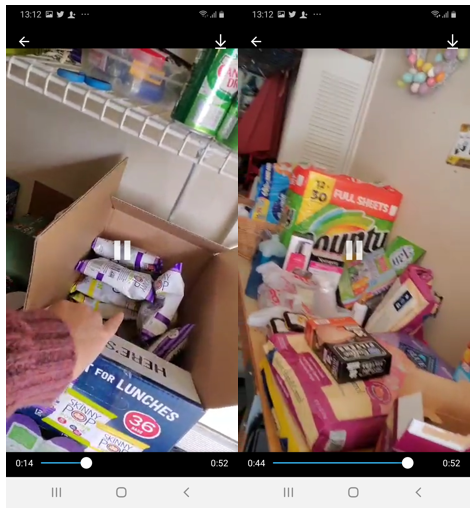

In the following data excerpt 1, a student has posted a video of her pandemic lockdown preparations, captured in her kitchen pantry. The student lists and shows the camera the products she has purchased from the grocery store:

Excerpt 1: My little store

Video transcript

((student waves to the camera)) hei kaikki. mun pieni kauppa. <hi all. my little store>

((Moves camera, shows products on the shelf.))

Popkornia hah. <popcorn hah> these things hah. ((looks up)) Paljon jutut. <lots of things> ((taps a can))

Teetä <tea> ((grabs a tea box, box falls on the ground from the pile of boxes; then moves the camera towards the ground))

Ensimmäinen teetä. <first tea> ((Waves camera around the room, then shows more products))

Okei, toivon sä hyvin. Moi moi <okey, I wish you are well. Bye bye>

Purchasing many items from the store in the beginning of quarantine (March 2020) was a typical survival strategy: preparedness for the situation seemed important during the unpredictable times. The student seems to be a little ironic about her preparations, because she has titled the video “My little store”, indicating that she almost has a small store at home now, because she has purchased so many items that occupy a great deal of space in her pantry. The student takes a moment to share her corona preparations with the class. The video seems spontaneous, unrehearsed, and unedited, a momentous sharing of the home interior. It is personal - it shows her face and invites other students to her kitchen. She ends the video in well wishes, a practice which is typical of the student chat data during the covid-19 outbreak.

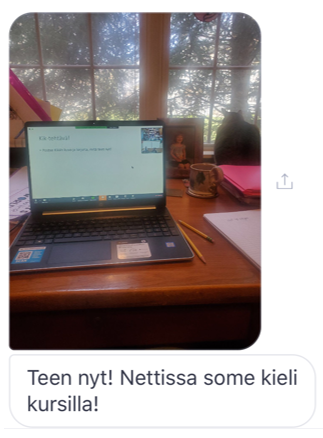

A common topic in the Finnish learners’ chat especially in the beginning of the pandemic outbreak is the sudden transition to remote study. The entries often focus on studying Finnish from home. The following is shared by a student during an ongoing class:

Excerpt 2: In the Finnish language course online

Chatting by using mobile phones can broaden the spectrum of possible learning spaces (see Neumeier, 2005: 175), as in this example, where chatting enables incidental learning to take place even at home. In excerpt 2, the student posts a “status update” <Doing right now! Online in the Finnish language course!>; the picture displays her desk with a laptop. The mobile chat allows the participants to communicate in an authentic way. This is connected to the instantaneous quality of chat: chat updates can be shared conveniently from outside of class and even from the classroom, which blurs the line between in and outside of class. The eagerness to participate in this chat made the language practice seem less like an exercise and perhaps more like informal sharing between peers. Studying online and sharing home office settings becomes a mutually shared experience for the language learners.

Another shared reality and shared experience for many North American university students in the beginning of the covid-19 lockdown was that students needed to return from their student residences to their permanent addresses. For many this meant a quick change of town, state or even country. Here, a student who has had to leave Canada and travel to her family home in the United States, writes an update:

Excerpt 3: In the US with family

The student writes: <I am home, in the US with family and I am really good!> The quick update informs the peers about her new location: she has safely managed to relocate, and she is alright. A peer replies <Good sounds…> stating that it is positive news to hear that she is home and well. During chat, it is possible for the students to change location and participate from different locations, without interrupting the flow of conversation.

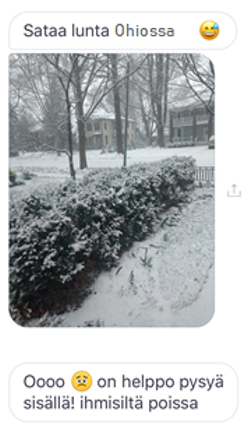

As students are in different places after the lockdown, they also share different weather updates from many distant locations around North America, which becomes a common chat activity. In addition, students share updates from proximity to their homes. In the following excerpt, a student starts the conversation by sharing a photo of a snowy scenery captured through a window in their home:

Excerpt 4: Easy to stay away from people

Although it is already late March, the entry features a snowy, wintery, and empty residential street. The comment says <snowing in Ohio> and is followed by an emoji with a drop of sweat in the forehead, indicating perhaps a sign of frustration. The other student’s response “oooo” implicates shock and confirms that the weather is surprisingly poor for the season. At the same time the following comment <it is easy to stay indoors!! away from people> indicates encouragement and a positive take on the situation: because the weather is not inviting, it is easier to follow physical distancing orders. During the corona spring, students mostly viewed the world from the warmth and safety of their home.

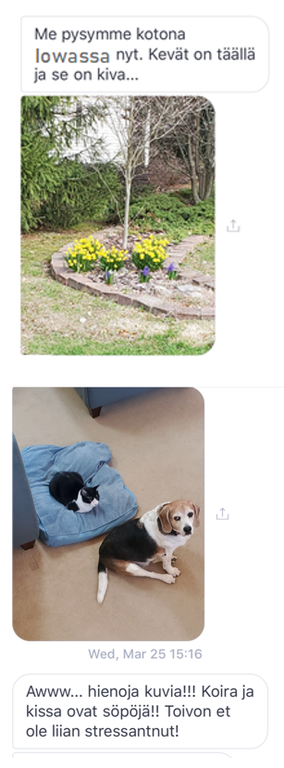

Later, another student publishes an entry which is also captured in the garden. In the comment the student writes that she is staying at home and comments that in her location, spring is already progressing: <We are staying home now. Spring is here and that is nice…>:

Excerpt 5: Home

Right after that she shares a picture of her two pets. A peer replies with a compliment <aww nice photos!! Dog and cat are cute!!> followed by a wish that her peer is not too stressed during the corona time. As the topic of physical and social isolation is prevalent in the chat throughout, peers often offer support. Although the peer’s comment about stress does not directly relate to these pictures it describes the common discussion topic and the mood of many participants during the lockdown times.

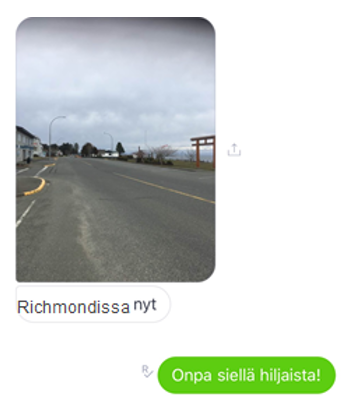

Throughout the chat, peers share glimpses of their lives after the lockdown featuring empty spaces in big metropolises, towns, city centers, rural areas, and nature. A common feature in all these entries is that no other people can be seen. In the following excerpt, a student shares an image from a quiet street in her hometown:

Excerpt 6: In Richmond now

The photo is captured through a car window; the brief comment says <in Richmond now>. A comment <how quiet it is> from a peer follows. The photo functions as a “location update” - the student is in her hometown where the usually busy streets are suddenly empty. In all the pictures that students are sharing of public places, people are safely indoors, and the places are empty. Here again, the shared image offers a window to each others’ experiences (see also Combe & Codreanu 2016: 123).

Due to the covid-19-time physical distancing health regulations, residents in North America where asked to stay home as much as possible and keep physical distance from other people outside their immediate family. In all the excerpts above, students have shared images from their current locations at or near their home. When the students go out, they share photos and commentaries from empty isolated places where there are no other people. The fact that the students are actively and genuinely participating in the class chat from these places shows motivation: via chatting they can direct their own learning into meaningful topics, learn things that are relevant to them and be in contact with other students (see Biggs 1995: 3−4).

Discussion and conclusions

In this article we have demonstrated some of the covid-19-related chat entries the students shared when seeing classmates in person was not possible. We have focused on the spaces Finnish learners discuss in the class chat and some of the discourses related to these spaces. During the covid-19 pandemic, students shared updates from, for example, homes, backyards, gardens, and hometown streets.

In what seemed like a spontaneous and authentic manner, students posted snapshots of their lives and engaged in real, meaningful, and supportive interaction in the target language, Finnish. Multimodal cues, such as photos and videos, supported this communication. The easy access to the instant chat allowed students to participate at their convenience, making the division between in and outside of class learning less distinct. As we have shown here, students shared authentic glimpses of their lives with the participants.

Remarkably, even amid the uncertain and perhaps stressful times, participants managed to keep their Finnish class peers updated of their activities, (re)locations and well-being. Meanwhile, the chat discourse also offered numerous opportunities to practice and learn Finnish. The objective of the task was participation in Finnish in a more relaxed and informal way, and thus we as instructors only observed but did not monitor the conversation. We observed different levels of activity throughout the chat from different students but there were no significant changes in activity after the transition to remote teaching.

The use of a mobile application enabled students to take language use and incidental learning with them wherever they went. They managed to keep in touch even in a situation where physical distancing was enforced, and students were abruptly located all over North America due the covid-19 pandemic. In this paper, we have demonstrated that with the easy access and usability of mobile devices, students can conveniently share snapshots from their lives and commit to a regular language learning practice that goes beyond the classroom and homework.

Elisa Räsänen, MA, is a Lecturer in Finnish language and culture at Indiana University, Bloomington, USA.

Anu Muhonen, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Finnish Studies at the University of Toronto, Canada.

References

Biggs, J. (1995). Assessing for learning: some dimensions underlying new approaches to educational assessment. The Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 41(1). s. 1–18.

Bogdanoff, M., Vaarala, H. & Tammelin-Laine, T. (2019). Perustaidot haltuun: älypuhelin osana aikuisten lukutaito-oppijoiden monilukutaitoa. Kielikukko, 39 (2), 2–9.

Jin, L. (2018). Digital affordances on WeChat: learning Chinese as a second language. Computer Assisted Language learning (1–2)31, 27–52.

Kelly S.W. (2012) Incidental Learning. In: Seel N.M. (eds) Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_366

Komppa, J. & Kotilainen, L. (2019) Mobiiliteknologia kielenoppijan apuna – esimerkkinä puheentunnistus ja Appla-sovellus. Teoksessa Kotilainen, Lari, Kurhila, Salla, Kalliokoski, Jyrki (toim.) (2019) Kielenoppiminen luokan ulkopuolella. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 114–142.

Lai, Arthur (2016). Mobile immersion: an experiment using mobile instant messenger to support second-language learning. Interactive learning Environments, (2)24, s. 277–290.

Lilja, N. & Piirainen-Marsh, A. (2019). Making sense of interactional trouble through mobile-supported sharing activities. In Kunitz & Salaberry (eds.) Teaching and Testing L2 Interactional Competence: Bridging theory and practice. Routledge, 260–288.

Lilja, N. & Piirainen-Marsh, A. (2016). Älypuhelimet oppimistoimintaa jäsentämässä. In A. Solin, J. Vaattovaara, N. Hynninen, U. Tiililä, & T. Nordlund (Eds.), Kielenkäyttäjä muuttuvissa instituutioissa - The language user in changing institutions. AFinLAn vuosikirja 2016 (s. 43–64). Suomen soveltavan kielitieteen yhdistyksen julkaisuja, 74. Jyväskylä, Finland: Suomen soveltavan kielitieteen yhdistys.

Li, J. L. (2018) Digital affordances on WeChat: learning Chinese as a second language. Computer Assisted Language learning (1-2)31, s. 27–52.

Neumeier, P. (2005). A closer look at blended learning – parameters for designing a blended learning environment for language teaching and learning. ReCALL, 17(2), 163–178.

Räsänen, E. & Muhonen, A. (2020) “Moi moi! Te olette siistejä!”: Chattailyä, itsestä kertomista ja yhteisöllisyyttä pohjoisamerikkalaisissa suomen ohjelmissa. In: Sirkku Latomaa & Yrjö Lauranto (edit.) 2020. Päättymätön projekti III. Kirjoitettua vuorovaikutusta eri S2-foorumeilla. Kakkoskieli 9. Helsinki: Helsingin yliopiston suomalais-ugrilainen ja pohjoismainen osasto, 82–98.

Vaarala, H. & Bogdanoff, M. (2019). Älypuhelimet aikuisten lukutaito-oppijoiden vapaa-ajalla. Kieli, koulutus ja yhteiskunta, 10(6). Saatavilla: https://www.kieliverkosto.fi/fi/journals/kieli-koulutus-ja-yhteiskunta-lokakuu-2019/alypuhelimet-aikuisten-lukutaito-oppijoiden-vapaa-ajalla

Wigham, C. & Chanier, T. (2015). Interactions between text chat and audio modalities for L2 communication and feedback in the synthetic world Second Life. Computer Assisted Language Learning (3)28, 260–283.