Towards sustainable bilingual-CLIL education through the three gifts of teaching

Julkaistu: 14. toukokuuta 2024 | Kirjoittaneet: Josephine Moate ja Pei-Fen Hsu

Content and Language Integrated Learning and Bilingual Teaching in Finland

Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) was developed in the early 1990s as a response to the need to improve foreign language education across Europe (Marsh, 2002). In a somewhat audacious move, foreign languages were added to subject studies to see whether this would improve language learning without undermining the studying of different subjects. Despite various challenges, CLIL as a dual-focused approach to education has been surprisingly successful and is considered a flexible way of improving language education (Ruiz de Zarobe, 2015). Finland, a CLIL forerunner, has been an important contributor to CLIL and the current national curriculum includes a specific chapter detailing how foreign languages can be used across the Finnish curriculum (EDUFI, 2014). To avoid using a foreign acronym in the curriculum, CLIL is referred to as “kaksikielinen opetus” – bilingual teaching. This seemingly simple turn is radical as it foregrounds the importance of bilingualism, that is using and acknowledging the importance of more than one language, and focuses attention on teaching, not learning. This turn provides an important opportunity to reconsider CLIL from a different perspective. To do this we draw on the recent work of educational theorist Gert Biesta and the three gifts of teaching (Biesta, 2022) with the aim of strengthening the sustainability of bilingual-CLIL education.

CLIL to date – the focus on learning through the 4Cs and the language triptych

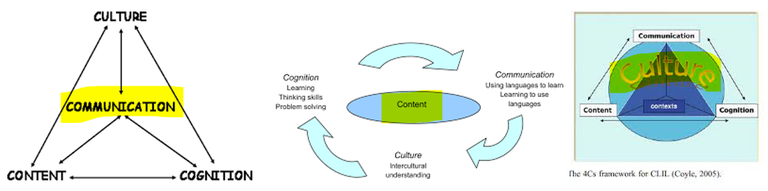

Useful tools often associated with CLIL are the 4Cs and the language triptych. The 4Cs highlight the importance of: Content as the substance of lessons, that is knowledge and skills; Cognition as different ways of thinking and engaging with content; Communication as the multiple ways in which language resources and guides learning and mediates relationships; and Culture as characteristic of the immediate, disciplinary and global community. Although subject and language teachers can approach the 4Cs in different ways, the 4Cs remain a fundamental feature of methodological guides for CLIL with each C playing a significant role in planning, implementing, and evaluating CLIL (Kohl et al. 2022).

Figure 1. Different configurations of the 4Cs with central C highlighted (adapted from Zydatiß , 2007; Spratt, 2017; Coyle, 2005)

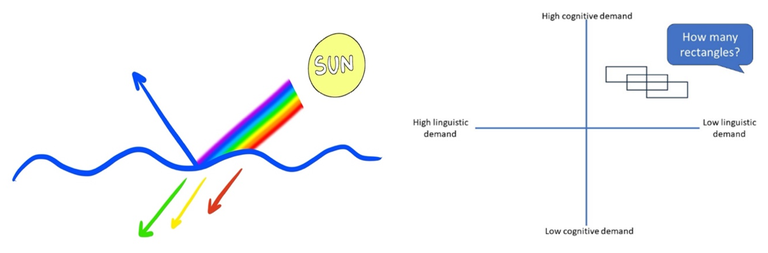

Over the years the relationships between the Cs have been variously reconfigured (Fig. 1). While the authoritative C of Content is drawn from the curriculum, it is through the Cs of Cognition and Communication that students access content. For instance, in art, teachers may let students describe the colour of the sea as they observe it in daily life, while in a science class, teachers may want students to understand how the reflection and absorption of light creates the blueness of the sea (Fig. 2). These two examples indicate how subject perspectives alter the way language is used and what meaning is intended. A dilemma CLIL teachers face, however, is to ensure quality thinking when communication is limited. The CLIL matrix (Coyle et al., 2010) indicates students can participate in higher order thinking with minimal vocabulary (Fig. 3), but at the same time many CLIL tools emphasize the importance and complexity of language in CLIL.

Figures 2. & 3. The reflection of blue light https://tips.clip-studio.com/zh-tw/articles/6224#author. The CLIL matrix with the added illustration of a mathematical task for young CLIL students

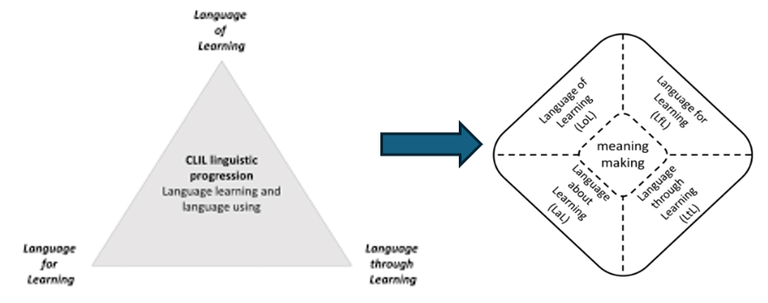

One recognized tool is the CLIL language triptych (Fig. 4) which highlights the importance of language for, of and through learning with the language about learning recently added to further promote ‘deep learning’ (Banegas & Mearns, 2023) ( Fig. 5). Through the language triptych both content and cognition become primarily ‘languaged’ phenomena and language is seen as an important way of deepening the process of learning. It is worth asking, however, whether placing learning at the centre of CLIL provides an adequate basis for sustainable bilingual-CLIL education. Indeed, the fourth C of Culture, based on intercultural understanding, is not so much about learning, as living with immediate and more distant others in a shared world. The C of Culture points to a wider educational purpose. Culture goes beyond individuals to shared ways of being, doing and knowing, without suggesting that individuals should be subsumed in or reduced to a cultural group. This fourth C acknowledges that cultural encounters are important and worthwhile, but often are neither easy nor without some discomfort, even disorientation (Lobytysna et al. 2020).

Figures 4. & 5. The original Language Triptych and the recently proposed Language Quadriptych (adapted from Banegas & Mearns, 2023)

Can sustainability be strengthened in CLIL through the gifts of teaching?

For CLIL to be sustainable we have to ask the existential question of how CLIL can enable students to ‘exist “in” and “with” the world, natural and social – … and do so in their own right… acknowledging that the world, …, puts limits and limitations on what we can desire from it and can do with it – which is both the question of democracy and the question of ecology’ (Biesta, 2022, p.3). As Biesta (2022) argues, framing learning as a process and deferring to learning as a judgment of educational success distracts from other important aims of education beyond the language of learning. One such feature is teaching, which tends to be reduced to facilitation by the language of learning. As many CLIL teachers know, however, teaching is a distinct practice that involves more than the facilitation of learning. In the following section we therefore turn to the gifts of teaching, as outlined by Biesta (2022), as a starting point for strengthening sustainability within bilingual-CLIL education.

Research highlights the courageous and often creative way CLIL teachers have sought to overcome the challenge of reduced language resources and limited materials. The gifts of teaching, however, go beyond creative responses to difficult situations to acknowledge the profound value and artistry of teaching. The three gifts of teaching are the gift of being given what you didn’t ask for, the gift of double-truth giving and the gift of being given yourself (Biesta, 2022). As teaching is often overlooked in educational and CLIL research, it is worth considering what the implications of these gifts are before focusing on CLIL. The first gift implies that a true gift is not self-given but comes from the outside, as a surprise, transcending expectations. This gift suggests that teaching should make the world of students bigger and richer, expanding their knowledge and understanding, and pointing their attention to something previously unknown. The second gift recognizes that when receiving something from the outside, it helps if the truth of the gift is also visible. In other words, teachers should make the conditions for truth from the perspective of different disciplines available to students, not just obliging students to believe that sea water is blue because an authority says so or because at first glance they think so, but rather because they are given the reason behind the phenomenon: that blue light is reflected from the surface of the water. The third gift recognizes the agency of students and respects the boundary line between education and indoctrination. This gift leaves the decision for how to be in the world to the student once the other gifts have been given. With these three gifts of teaching, school can be seen as a ‘halfway house’[1] beyond the care of a familiar home and protected from the carelessness of the wider world. In this ‘halfway house’ habitual ways of being, doing and knowing are interrupted and suspended and new ways of thinking and understanding nourished, as students are given the space to think for themselves how to be in the world – to be a self, as Biesta says. How then to receive these gifts in CLIL?

The gifts of bilingual teaching

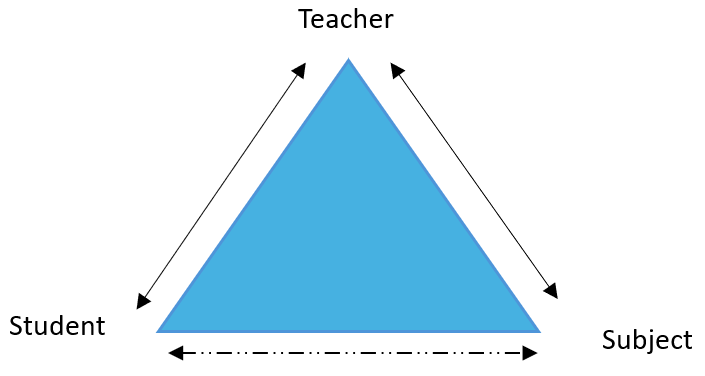

Returning to the 4Cs, the first gift of teaching is present in the Content – knowledge and skills which transcend students’ current understanding, neither limited to what students already know nor want to know. This first gift of teaching in CLIL is particularly apparent when teachers direct students’ attention to phenomena beyond students’ existing knowledge or language. CLIL teachers cannot assume that even everyday language associated with phenomena is part of students’ existing repertoires. With the newness of the phenomena comes the allowance for surprise, wonder even, as students encounter something entirely new. The first gift therefore expands CLIL cognition beyond the lower and higher order thinking skills of LOTS and HOTS. CLIL teaching should not remain beyond the comprehension of students, but being disarmed in the face of a new encounter creates an important space for teachers to begin weaving a relationship between students and subject (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Teaching as establishing a relationship between subjects and students

Establishing a relationship between the student and the subject connects with the second gift of teaching and complements the extensive work done in CLIL to make the frame of knowledge available to students through language aware teaching. With ‘double-truth giving’ (see Fig. 7) students are not socialized into simply believing or denying what they are told or assume, but they are given the conditions for recognizing and judging truth. Teachers do not simply present students with knowledge but invite students to stand within the frame of knowledge. That is, teachers share how knowledge is formed and framed through language and other discipline-based practices. This gift highlights the profound importance of teaching and gives students the chance to test what they are able to do when they encounter something new in the real world. In CLIL, teachers create a safe environment for students to be socialized through the sharing and examination of different ideas, ways of thinking and cultural contexts. The second gift requires integrity and values diversity.

Figure 7. The gift of double-truth giving

The third gift is in the space given to students to grow up and be subjects in their own right, not just subjected to the demands of expert others. The third gift seeks to avoid the narcissism of approaches based on learner interests alone and the despotism of approaches which leave little space for students to think and act for themselves. The third gift seeks to strike a balance between world-destruction and self-destruction (withdrawing from the world) (Biesta, 2022). This third gift enables students to be a self, and prepares students to be at home in the world through their education. In CLIL, the connection between cognition and communication, the opportunity for students to communicate as their understanding develops, to share and debate together, opens possibilities of realizing oneself through sustainable relationships with others and the wider world. Indeed, as bilingual-CLIL students are all the more vulnerable due to working through an additional language, as they embark on their educational journey and there is an even greater need for good teaching within an empowering community. This need resonates with the vision of the third gift.

A continuing dialogue towards sustainable bilingual-CLIL education

In this short article we have re-viewed some basic features of bilingual-CLIL education through the three gifts of teaching as presented in Biesta’s (2022) World-Centred approach to education. This approach highlights the importance of students’ relationship with the world calling for ego-centred learning to be replaced with eco-centred education. The three gifts highlight the paramount importance of teaching, going beyond the language and limited frame of learning. While CLIL tools to-date have helpfully drawn attention to the importance of language and learning in education, we suggest that for bilingual-CLIL education to be sustainable, the profundity of teaching needs to receive greater attention and to not remain hidden behind the language of learning that tends to dominate CLIL today.

[1] There is a significant philosophical tradition behind this statement that schools as a halfway house between home and the world drawing on insights from Hannah Arendt’s Crisis in Education and the limits of education, as well as others.

Josephine Moate is a senior lecturer based in the Department of Teacher Education at the University of Jyväskylä. Josephine’s research interests include pre- and in-service teacher development, the role of language in education and the theorisation of education.

Pei-Fen Hsu is a doctoral researcher based in the Department of Teacher Education at the University of Jyväskylä. Pei-fen’s doctoral research explores what a World-Centred Approach to education could contribute to bilingual-CLIL education in Finland.

References

Biesta, G. (2022). World-centred education: A view for the present. New York: Routledge.

Banegas, D. L., & Mearns, T. (2023). The Language Quadriptych in content and language integrated learning: Findings from a collaborative action research study. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 0(0), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2023.2281393

Coyle, D., Hood, P., & Marsh, D. (2010). CLIL: Content and language integrated learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Coyle, D., & Meyer, O. (2021). Beyond CLIL: Pluriliteracies teaching for deeper learning. Cambridge University Press.

Dalton-Puffer, C., Hüttner, J., & Llinares, A. (2022). CLIL in the 21st Century: Retrospective and prospective challenges and opportunities. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education. 10(2), 182-206.

Finnish National Board of Education. (2014). National core Curriculum for Basic Education.

Kohl, J., Marjanen, A., Routio, H., Rusama, J., Räisänen, R., & Salomaa, R. (2022). Handbook for Bilingual Education-English-enriched teaching and learning-Grade 5-6. City of Helsinki - Education Division. https://aoe.fi/#/materiaali/2470

Lobytsyna, M., Moate, J., & Moloney, R. (2020). Being a good neighbour: Developing intercultural understanding through critical dialogue between an Australian and Finnish cross-case study. Language and Intercultural Communication, 20(6), 621-636.

Marsh, D. (2002). CLIL/EMILE-The European dimension: Actions, trends and foresight potential.

Nikula, T., Skinnari, K., & Mård-Miettinen, K. (2022). Diversity in CLIL as experienced by Finnish CLIL teachers and students: matters of equality and equity. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 1-14.

Ruiz de Zarobe, Y. (2015). The effects of implementing CLIL in education. Content-based language learning in multilingual educational environments, 51-68.

Spratt, M. (2017). CLIL Teachers and their Language. Research Papers in Language Teaching & Learning, 8(1).

UNESCO. (2021). Reimagining our futures together: A new social contract for education. UN.

United Nations (UN). (2015). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. UN.

Zydatiß, W. 2007. Bilingualer Fachunterricht in Deutschland: eine Bilanz. Fremdsprachen Lehren und Lernen, 36, 8–25.